Most of us have probably seen clips of the 1933 film version of King Kong. It’s one of the most famous black and white monster movies ever made. In the iconic final act, the giant ape carries a damsel to the top of the Empire State Building as fighter pilots circle overhead, attempting to shoot down the beast.

Today, the scene doesn’t seem all that impressive from a cinematic perspective, but it was the Star Wars of its day. The audience would have gasped not only at the giant gorilla, but also at the fighter planes buzzing around the Empire State Building, shooting at it. After all, war planes were less than twenty years old at the time, being first used during World War I.

The movie’s director, Merian C. Cooper, knew what he was talking about when he created those fighter plane scenes. He had spent his youth as a pilot during the First World War. However, his claim to military fame came largely from founding a Polish-American fighter squadron that helped defend Poland against the Soviet Union during the early 1920s.

Pułaski Reborn

When one learns that an American director from the 1930s with the last name of Cooper risked his life fighting for Poland, the first question is why. After all, Cooper was born in Jacksonville, Florida, and there’s nothing Polish-sounding about his last name. In fact, his family had been in the United States for generations. Why would an American boy like Cooper know or care about a country 4,600 miles away?

The answer lies, perhaps, with Cooper’s family connection to Polish General Kazimierz Pułaski, who had fought and died for America’s independence during the Revolutionary War. Cooper’s great-great grandfather, John Cooper had fought with Pułaski at the Battle of Savannah, during which the latter was fatally wounded. According to Cooper’s family legend, John Cooper carried the dying Pułaski away from the battlefield. If that’s true, then it’s possible that the most famous Polish-American in history died in the arms of Cooper’s ancestor.

Whether that story is myth or fact, it, along with his innate thirst for adventure, likely played a role in Cooper’s decision to help Poland. In poetic fashion, Cooper would be completing a circle of sacrifice–just as a son of Poland had once fought for America, so too would a son of America fight for Poland 140 years later.

Forming the Kościuszko Squadron

Cooper excelled as a pilot almost from the moment he went airborne. He entered pilot school in Atlanta in 1917 and graduated at the top of his class. Shortly after, he shipped off to France to serve in the United States Army Air Service, where he learned to be a bomber pilot. After his plane was shot down in flames in September 1918, Cooper miraculously managed to land and survive.

The war ended in November 1918, but Cooper wasn’t done seeking adventure. He went to Poland to do humanitarian work as a member of the American Food Administration. It’s at this time that he likely fell in love with the fledgling republic.

From 1918-1920, Poland was beginning to recover from more than 120 years of foreign rule. Prior to World War I, Poland had been partitioned by Germany, Russia, and Austria-Hungary. All three occupying powers collapsed after the war, allowing Poland to win its independence with international support.

Trouble wasn’t far, however. Russia, the largest occupying power, had mutated into the Soviet Union and aimed to spread its communist revolution into western Europe. No sooner had Poland regained freedom than that freedom was put to the test.

Correctly suspecting an impending Soviet invasion, Poland launched a preemptive strike against Soviet-controlled Ukraine in what became known as the Kiev Offensive of April 1920. Although the Poles managed to seize the Ukrainian capital of Kiev, their victory was short-lived. The Soviets responded with a powerful counterattack that threatened Poland’s newfound independence.

Cooper was in Poland during these tumultuous times and decided he needed to act to protect his adopted country, perhaps, as mentioned, to repay the sacrifice of General Pułaski. After meeting with Polish general, Tadeusz Jordan-Rozwadowski and the leader of Poland, Marshal Józef Piłsudski, Cooper was given permission to form a fighter squadron of American pilots that would fight for Poland.

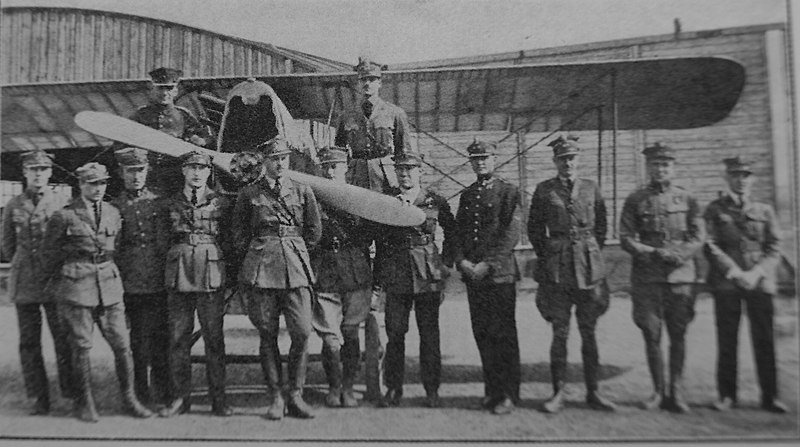

In a move analogous to the plot of The Magnificent Seven, Cooper traveled to Paris to recruit American pilots who had hung around after the war. In this case, he recruited eight volunteers and formed the Kościuszko Squadron with Major Cedric Fauntleroy in September 1919. The squadron was named after another Polish-American Revolutionary War hero, Tadeusz Kościuszko.

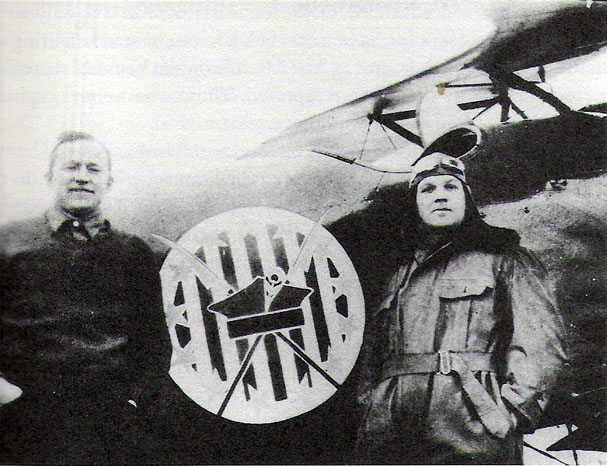

The Official Emblem of the Kościuszko Squadron. In the middle is a traditional Polish cap (rogatywka) crossed by two scythes representing the weapons wielded by Polish peasants during the Kościuszko Uprising of 1794. The stars and stripes represent the American flag.

Eventually, 21 American pilots joined the squadron, along with some Poles. The extra pilots enabled Cooper to create and take command of a sub-squadron, which was named after General Pułaski. Initially, the squadron primarily flew Albatros D.III fighters. It also made unique use of railroad cars that were specially designed to transport the planes.

After the Poles captured Kiev in April 1919, the Russian First Cavalry Army, under the command of Semyon Budionny, began a massive counterattack that drove them back westward. This series of events eventually culminated in the Polish-Soviet War of 1920 where, ultimately, the Poles defeated the Soviets at the Battle of Warsaw, foiling their plot to spread communism to the west.

Cooper and the Kościuszko Squadron played a key role in reconnaissance and ground attacks against Budionny’s cavalry, providing critical support for Polish troops on the ground. In most engagements, the squadron would fly low against the enemy, raining down machine gun bullets on the scrambling Soviets.

One of the squadron’s proudest moment came in defense of the city of Lwów in August 1920, where the American pilots slowed the Soviet advance, giving the Polish Army time to repulse the Red Army’s assault on Warsaw further west. Later that month, during the Battle of Komarów, the American pilots assisted in the near-destruction of Budionny’s Soviet cavalry.

Cooper himself couldn’t participate in these final acts of the Polish-Soviet War, as his plane was shot down in July 1919. Captured by the Soviets, Cooper spent nine months in a prisoner-of-war camp until he escaped and walked more than 400 miles to Latvia, where he was finally rescued. For his heroic service, Cooper was awarded the Virtuti Militari, Poland’s highest military decoration, by Marshal Piłsudski.

After his service in Poland, Cooper returned to the U.S., where he worked as a journalist for a time before becoming a movie director. The rest is history.

Returning the Favor

By organizing the Kościuszko Squadron and helping defend Poland, Cooper symbolically returned the favor Poland had given America in General Pułaski. The squadron itself continued into the future. During World War II, it was reorganized into the No. 303 Squadron RAF, which became the most successful squadron in the Battle of Britain.

Cooper’s story exemplifies the deep connection the U.S. has had with Poland throughout history. The two countries have long been allies in their fight for freedom and nationhood. His story is also a living testament to the allure Poland has for Americans. Whether one is Polish, or a homegrown American boy like Cooper was, it’s easy to fall in love with Poland.